I can draw pictures. That’s something I can do. I could sort clothes in the L’Auberge du Migrants warehouse, or distribute donations in the Calais Jungle, or carry firewood and build benders in the Dunkirk refugee swamp, but I decide to draw pictures, not of people, but for people. For people who have very little; not even a country to call their home.

I pack drawing inks because once they’re dry, they won’t run. I buy thick cartridge paper to make the portraits more durable, and plastic sleeves to protect them from the drizzling damp. I head out into the camp at Calais.

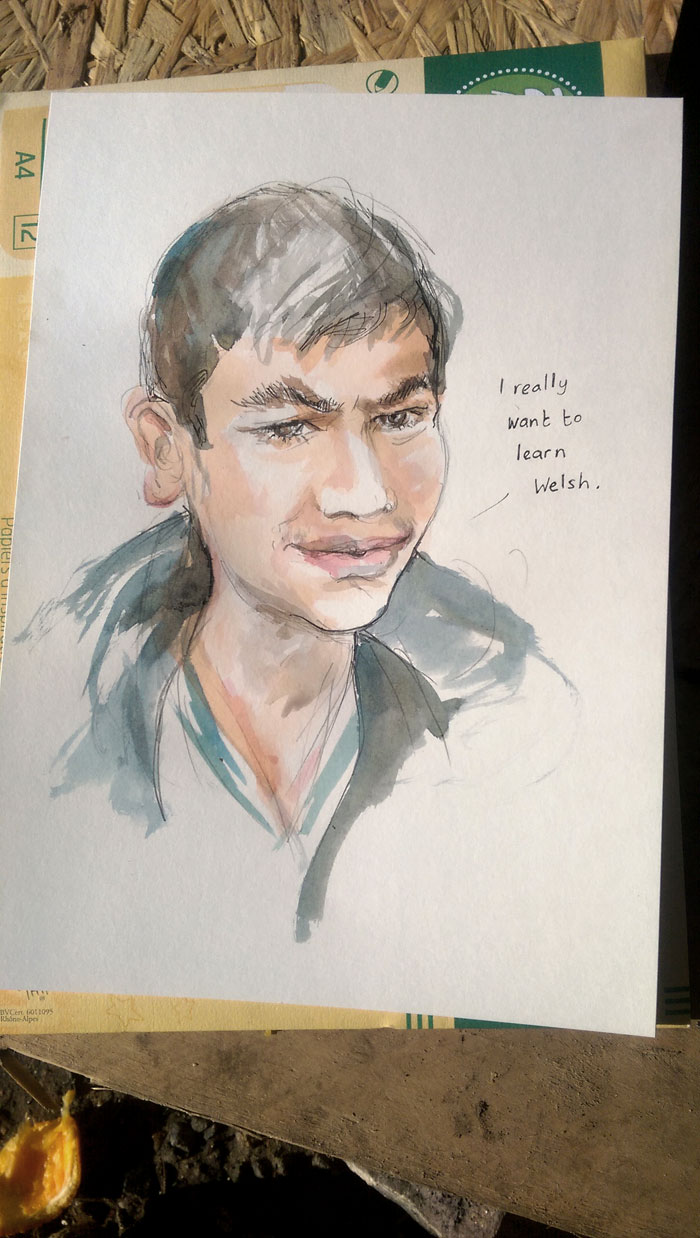

Jamshid is being interviewed by one of the L’Auberge des Migrants volunteers about the announcement that the authorities are to bulldoze much of the camp, including the newly-constructed Baloo youth centre where he spends his mornings. “I will one-hundred per cent go crazy” he says. “Before this was here, I was all the time in my caravan all the days. So bored!!!” His English is fluent and animated. His dark eyes flash with amusement. Where are you from? “Afghanistan.” How old are you? “Fourteen.” Have you any other family here in the Jungle? “Oh yes! My little brother.”

Why do you want to come to the UK? He answers with a child’s impeccable logic: “why not?”

He sits for a portrait. Jamshid speaks three Afghan languages, some Turkish and is learning French and English simultaneously. He is serious about wanting to learn Welsh – we find a Welshman to teach him and he starts that day. I’m not sure his picture does him justice, but I waft it dry and hand it over. I take a snapshot. He gets to keep the sketch.

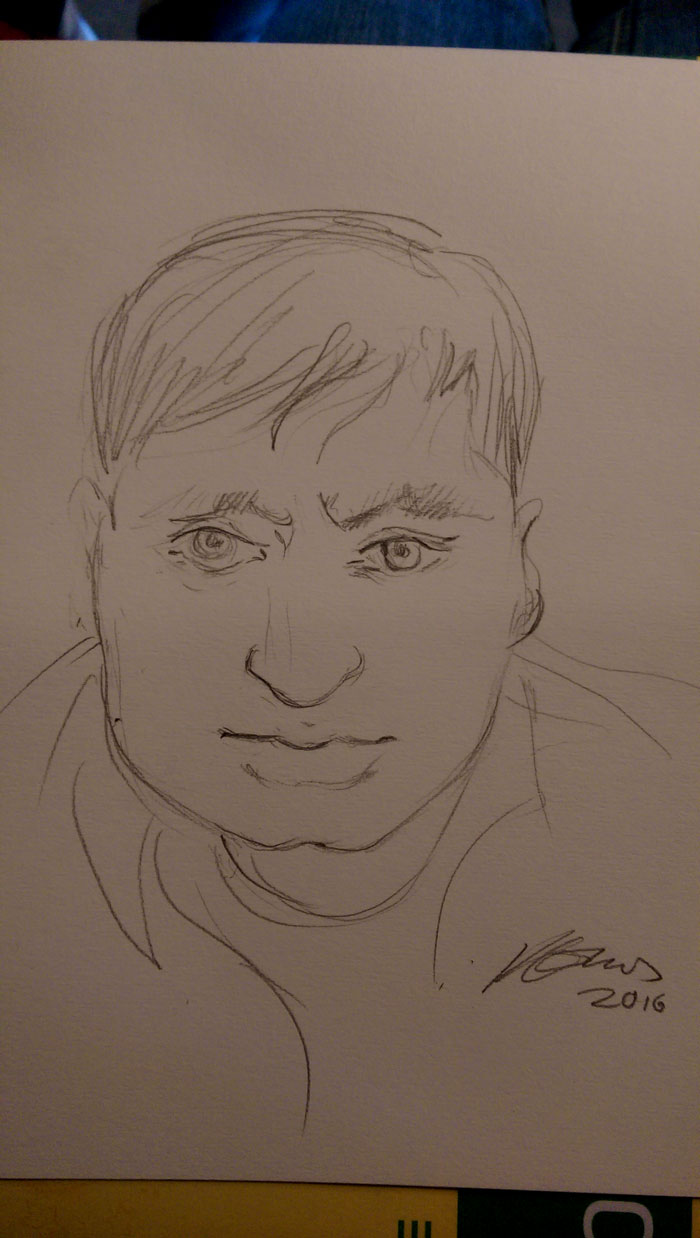

Jamshid’s friends crowd round. My next sitter? subject? victim? is 13 years old. He has a little sprinkle of acne just starting around his nose.

He shrugs apologetically when I try to engage him in conversation. “Very little English”. I ask someone to ask him what he wants to do when he’s older. “I don’t think that far” comes the reply. What does a child think of when he’s living in a rain-sodden refugee slum in a hostile country, and his family is five thousand miles away?

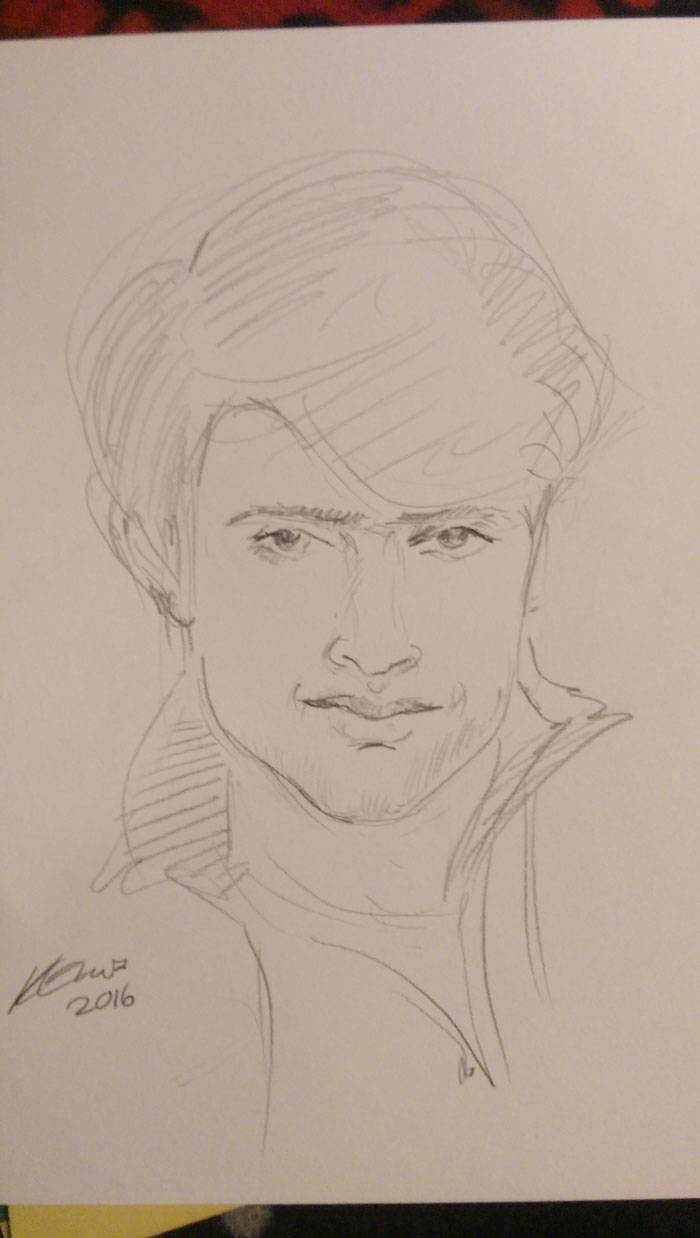

“Me now!” His best friend plonks himself down on the plank in front of me.

Don’t be deceived by those doe eyes. The child is an absolute imp.

“This child is like a ghost” someone tells me later when they see his picture on my phone. “You look, he is there. You turn the corner, he is there again.” Together with his impassive best friend (above) they roam the Jungle on bikes, generally getting up to anything and everything that a complete lack of family supervision will allow. The kid is 12 years old. This is state-sanctioned child neglect.

(If you’re intrigued as to why Afghan parents are handing their life-savings over to smugglers to bring their children to Britain, read this pdf from the UNHCR. It’s from 2010. This is not a new problem.)

Old-before-his-time Doe Eyes is not particularly impressed with his picture. He puffs out his cheeks to indicate that he thinks I’ve made him look like a hamster, but he pockets it anyway, with a grin.

Ben, the youth leader, leads the boys away to three hours of classes at the Jungle Books classroom (also scheduled for demolition). Ben is one of many volunteers here who came for a weekend, then jacked in their lives back in the UK and threw themselves into life in the Jungle. While we can’t change UK immigration policy (well, not overnight) we can do what we can to alleviate this humanitarian emergency. A situation that the French police have exacerbated by forcing thousands of vulnerable people to live on a rubbish tip. And now they’re planning to bulldoze the charity-funded spaces and places that volunteers have built to remedy the situation… And breathe!

Like the art school. The Ecole des Metiers des Artes. It’s a unique piece of architecture that appears to have been sown rather than constructed. No right-angles anywhere, but in a good way. I have arranged to meet someone here who asked me yesterday if I could draw a picture from a mobile phone.

I spend an hour drawing this picture. Or rather, I spend forty minutes drawing this picture, and twenty minutes jabbing the cracked mobile-phone screen to stop it from going black every thirty seconds.

“She is beautiful” I say to the phone’s owner. “I hope you tell her so every day.”

“Really? You think I should tell her?”

“Yes! Every day! My husband tells me that I’m gorgeous each time he sees me. It’s the secret to a happy marriage. When did you last see her?”

“Six years ago.”

Six years. The glib phrase “refugee crisis” is too small to contain all the multiple narratives, all the tragedies, all the epic odyssies. Six years. I can’t really comprehend it.

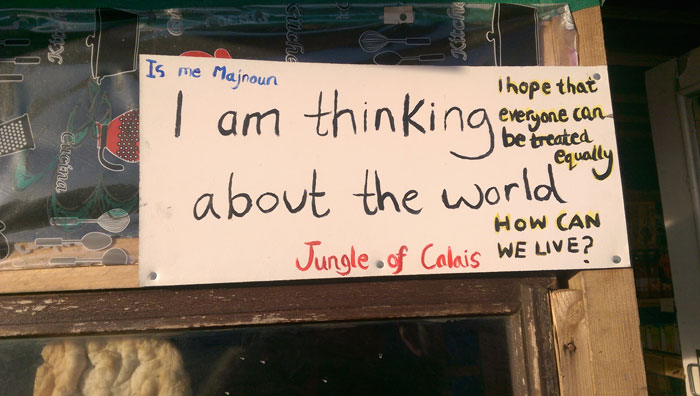

I should really head back to meet my friends. The evening is drawing in and the noise and bustle and nervous energy in the camp builds. The generators kick out petrol fumes. Music blares out of the cafes on the main drag. A man I’ve met earlier – “Call me Crazy eyes!” – grabs me by the shoulders. He wants to show me a sign he has made:

Laughing: “OK, I’ll take a photo.” He hustles me into the cafe. I’m amused. I know this is against my better judgement. He hands me a plastic beaker of sweet milky tea and gestures me to sit up on the wide bench against the wall and kick off my shoes.

I decide to turn this around. “I’ll draw your picture, yes?” Just a quick pencil sketch.

Crazy eyes.

It’s really getting dingy now. The petrol fumes don’t help the taste of the tea. Of course his friend wants a picture too. He’s wearing all-white, which is pretty damn classy in the Jungle. I can tell he really wants to look like a film star.

“No, no, I can’t draw any more pictures. I am meeting my Husband. Now!” I confirm that they’ll pay for my tea in exchange for the sketches. I can hustle too. Grinning, I skip off into the dusk.

The boys made me promise to come back the next day – “You draw my picture yes?” “Tomorrow! Tomorrow!” – and so the next morning I head back to the youth centre. It’s a great building, insulated, heated, and kitted out with a pool table. Designed and imported from Scotland, at a cost of £5,000, it was in use for precisely one week before the eviction notice was served.

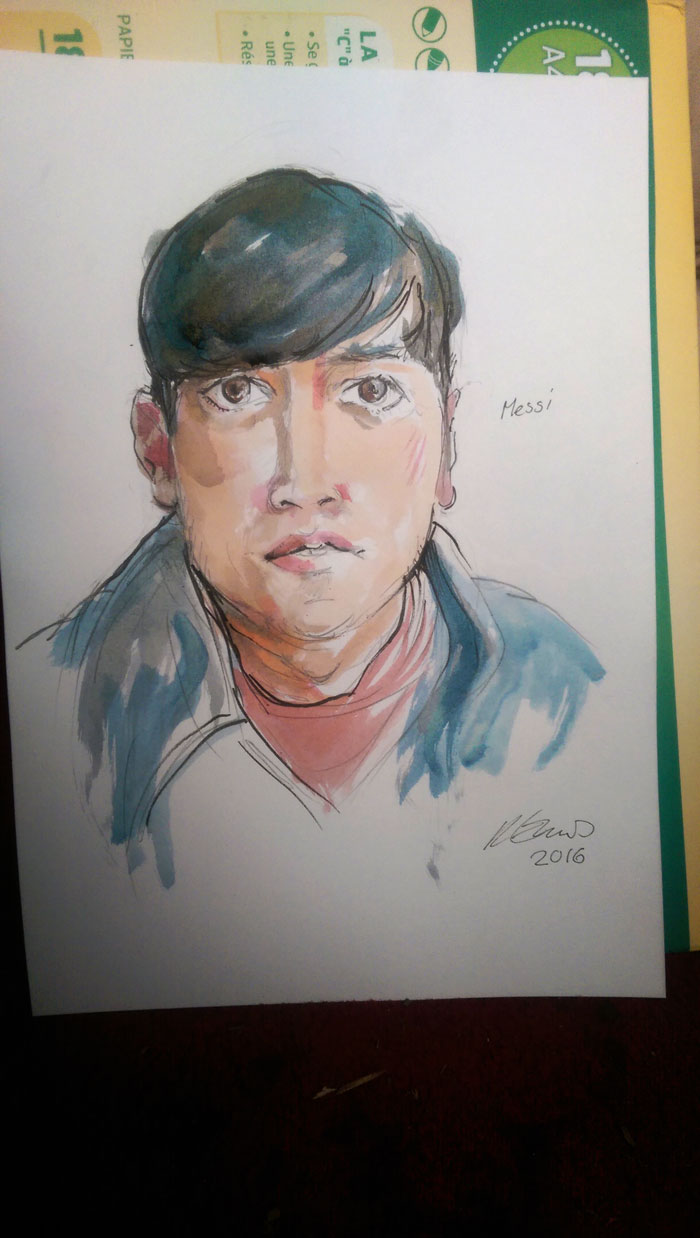

This fifteen-year-old lad is the first. He whips his hat off and rearranges his hair, compulsively and nervously – hair styling is important to these boys. We then mutually, multilingually agree that I won’t paint the massive cold sore on his upper lip.

Of course, all his friends file past as I draw and, in a variety of languages, point out that I’ve forgotten to draw the massive cold sore on his top lip.

He wants me to include his Arsenal shirt, but I have no yellow ink, so he makes me sign it “Messi” instead.

At this point the boys decide that I should have my picture taken too.

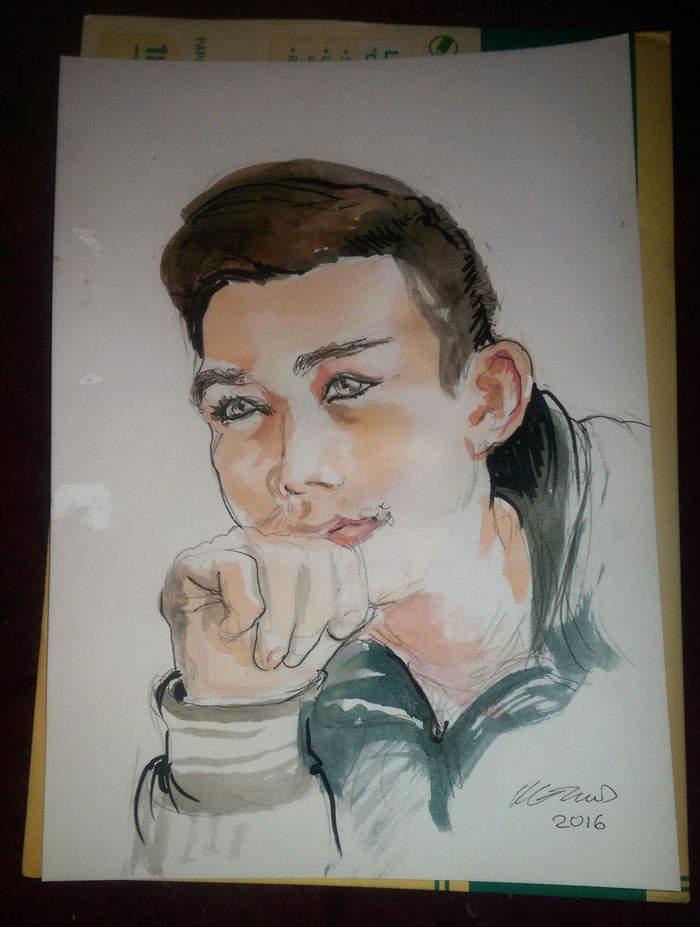

This next kid tells me he’s 12, but Ben says he also says he’s 13. Splitting hairs really. Carefully arranged and coiffured hairs at that.

His eyelashes are thick and dark. He has the slightest downy fluff on his upper lip. His ears are delightfully rounded – they look padded. I wonder idly if they are his mothers or his fathers ears… if they’re still alive… how long it has been since he saw them… when he’ll see them again… if he ever will…

It’s a tricky pose, and this picture takes me a while. It’s time for the boys’ lessons again and they are haphazardly shepherded away.

I wander over to the Good Chance Theatre Dome. Sue runs an art space under a polythene geodesic structure in the entranceway. Bizarrely, she lives down my road in the UK, but we’ve only ever met in Calais. She encourages me to grab a seat and crack out the drawing inks.

A man ushers a child into the chair opposite and I start to draw.

This is a very cute kid, but it’s hard to coax a smile out of him. Overwhelmingly, he looks wary. He’s not sure what or why adults do things, but they’re not to be trusted. He’s only six years old.

The man with him insists that I sign it: Ahmad. “Your son?” I say. “No, no, it’s my brother.” Bloody hell! Another motherless child! They’re everywhere! I haven’t met any kids here who aren’t effectively orphaned.

Man-in-white-tracksuit from the cafe last night comes in. He sits down in the chair: “The picture you make of me is no good. Another one!” Well, firstly, I’m not drawing anyone twice, because it’s boring. And also, if you do want me to paint your picture, don’t tell me that my pictures are no good. There’s a good humoured stand-off, where I slowly pack my inks away one, by one. He relents and shoves someone else into the chair. “You draw my little brother.”

This lad has a funny, squashed face, with one eye set higher than the other, and his chin set awry. He looks at me like he knows this. I paint him handsome. The chain around his neck has an enamel Afghanistan medallion on it, which he has tucked away next to his heart. So, that blagging, sharp-dressed white-track-suit man has a little brother in his “care”. A brother who is only thirteen years old.

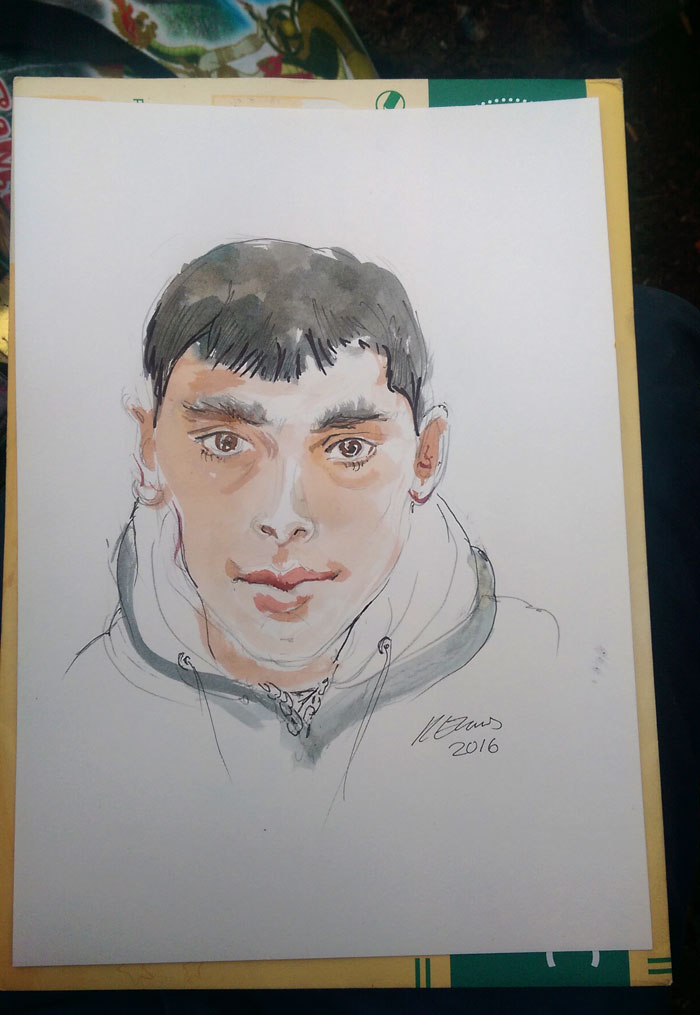

There is a pause. A man sits down shyly, pulls off his hat and scarf and carefully slicks his hair back. It’s a little long, by Afghani/Kurdish standards (I didn’t ask which he was) so he can’t afford to see the camp barber. He is calm, and quiet and sits perfectly still.

I ask him how old he is. “Eighteen” he says, sweetly. So technically not a child then, but from my 43-year-old perspective, no less in need of protection. I hate to think of him risking death in the lorry backs or on the train tracks.

By contrast with my current model’s serenity, someone is trying to attract my attention. A lad is clowning around, frowning, making monkey noises. “Look at ME!” he shouts, and I don’t and I tell him that if he wants me to paint him next, he has to let me finish this picture first. “Look at ME!” I glance up at his antics. Yes, sure I’ll draw his picture but I severely doubt he can sit still.

I’m wrong.

He’s thirteen too.

Sigh.

I didn’t plan this! I didn’t specify that I would go out to find unaccompanied refugee children: the spectacularly neglected, traumatised and abandoned. I’m sitting in a general access art space, it just happens to be that with a sort of synchronous, poetic resonance, the #ChildrenofCalais have come to me.

I’m really cold now. One last picture. Let’s buck the trend. A guy says “Sure, I’d like a picture.” We chat away – hang on, he has a Birmingham accent! – it turns out he’s a taxi driver from Wolverhampton, just over for the day. So he’s not actually a camp resident, and I point out that technically, he now owes me a taxi ride when I’m next in the Midlands. What’s he doing here anyway? He’s here because of his nephew, who is fourteen years old, and living here alone. I’m not making this up!

“We signed all the legal papers. I thought that meant we could take him away, but they tell us it could take months. So we have to leave him here. It’s not fit for a dog to live here.”

Under the Dublin regulations, refugees should be able to be reunited with family members in the UK. Recent legal precedent should allow these children to travel in safety to Britain, but the Government has appealed the decision, leaving these kids in legal limbo. And the bulldozers are on their way.

Here’s a petition urging the UK and French governments to fulfil their basic responsibilities with respect to unaccompanied refugee children.

And here’s my taxi-driver friend standing in the art dome (demolition scheduled for next wednesday) and looking very unsure about his portrait. “Is that really what I look like?” You be the judge.

9 Comments on “Children of Calais.”

Great job Kate and it was wonderful to bump into you x

Thankyou..this is a beautiful loving potrayal of these little boys/ young men and there stories. Was there last week too and recognise some of them x

@Kate you are doing a beautiful thing in an ugly world x

Kate, it’s brilliant what you’re doing! Make sure you go on with it – and keep writing – your writing is so lively and combined with the lively portraits (you’re good at getting the likeness – that’s a gift) you’re introducing us all to people we can carry in heart and mind. Surely, soon, the authorities will show some compassion and help the children move to join their families? It’s shaming to be a middle class Brit human at the moment, but your work spreads a lot of hope. x Naomi aged 76

Beautiful spirit, soul, and work. We learn so much when we do such work. You have made a difference to each of these young people. Not able to scoop them up and take them to a new home, but definitely able to have a smile, share a moment that will be remembered forever in the pictures you have given them; a moment that may at some time be the difference between holding strong and letting go.

We each do what we can and every bit builds the tapestry.

Thank you.

Wonderful Kate. Very moving. Your drawibgs really reach out to my heart. How can this be allowed to continue?

I’m very moved by your portraits, Kate. Seeing them and reading your words makes the situation in Calais much more real – and therefore far more poignant. I feel like I know these young men. And I think you’re giving them a lot by drawing them. Keep it up! x

I love what you are doing, Kate. This reminds me of the power of Humans of New York, but is not transactional and your connection with the sitters is clear. Great work.

Ah, this is beautiful. Fantastic writing too! I found you via Karrie Fransman, and have been drawing portraits of Afghan refugees here in Stockholm, but in the safe, cosy dependable Café used by the Red Cross every Tuesday in the year. Wonderful portraits, truly inspiring. I must buy your book Threads!