[This article was first featured in the journal e-international relations]

My name was put forward as the author/artist of Red Rosa, a graphic biog-raphy of Rosa Luxemburg precisely because the editor Paul Buhle was looking for a female graphic novelist to take the project on. This article will explore how I form representations of Luxemburg’s gender identity in the work and how my lived experiences as a middle-aged woman have informed those constructions. As a comics artist, working with a combination of sequential text and images, I use both textual, linguistic, lineal, ‘left-brain’ formulations and concepts, and also visual, non-verbal, ‘right-brain’ imagery in my work. This article examines both.

For copyright reasons, the samples of artwork included are rough ink work, not final art from the book, but they give an accurate impression of the finished images. Page references are to the 2015 Verso first edition.

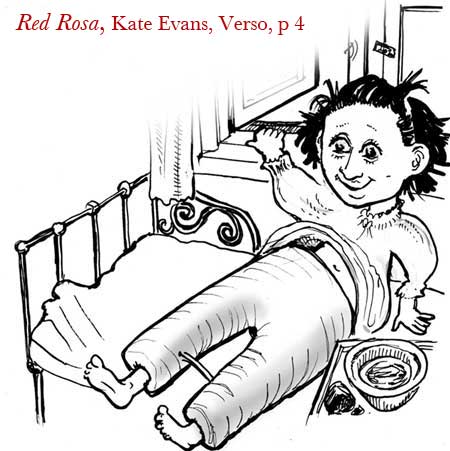

One of the first images I present of Luxemburg in the book is of her as a five-year-old child encased in a heavy plaster cast.

It is a significant event in her childhood, but it also has lasting ramifications for her conception of herself as a woman. The plaster cast treatment is unsuccessful, and Luxemburg suffers from a lifelong visible disability – one leg is shorter than the other and she walks with a pronounced limp. This deformity in her hip, I believe, shapes both her and her family’s expectations of what she can achieve as a woman. In effect, it renders her unmarriageable, which in turn, grants her the freedom to pursue an ‘unladylike’ academic career with parental support. This intersectional reading of the multiple oppressions to which Luxemburg was subject, reveals how one, surprisingly, liberates from another. I retain the image of Luxemburg wearing one fat-soled boot throughout the book even though the photographic record shows that she abandoned wearing ‘corrective’ boots after childhood. I needed to give the reader a constant visual reminder of her disability, as I was unable to draw her limp.

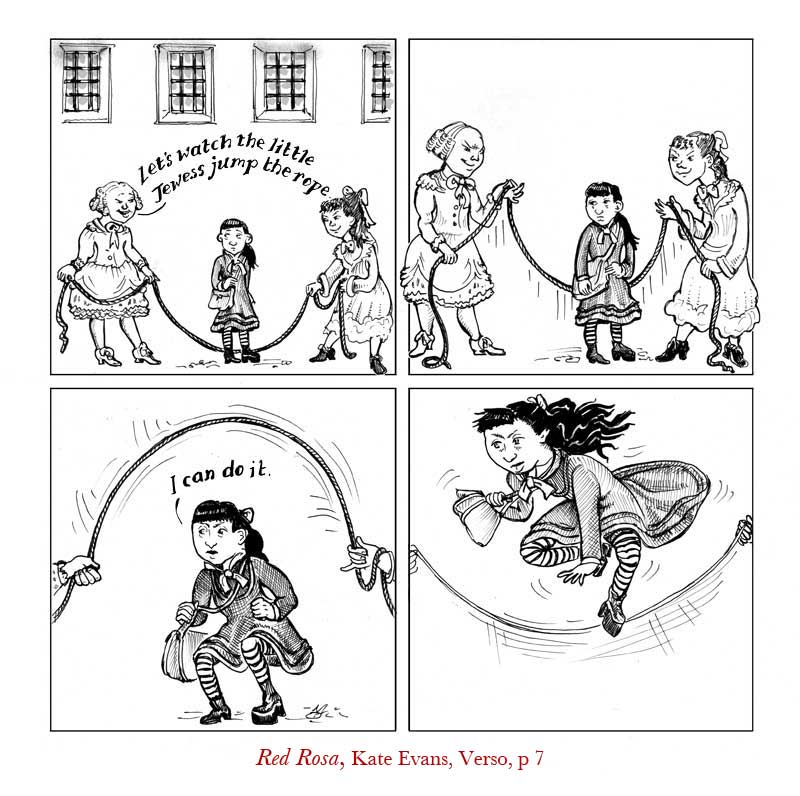

Very shortly afterwards, however, the book provides a simple visual metaphor for Rosa’s attitude towards societal restrictions, in this case, the multiple handicaps of disability and anti-Semitism. The visual contrast between tiny Jewish Rosa and her privileged richer Christian peers is stark in this image.

Rosa wins a scholarship to the Gymnasium. Only a few places are allocated to Jews. They set the bar higher for them.

Little Rosa studies hard. She can’t afford to trip up.

[Red Rosa p 7]

I return to this image of ‘Luxemburg leaping’ repeatedly in the book. It is so unlike the usual restricted, almost static images we are familiar with of Victorian heroines from costume dramas. It makes it clear that we are dealing with someone who is prepared to leap over conventional boundaries.

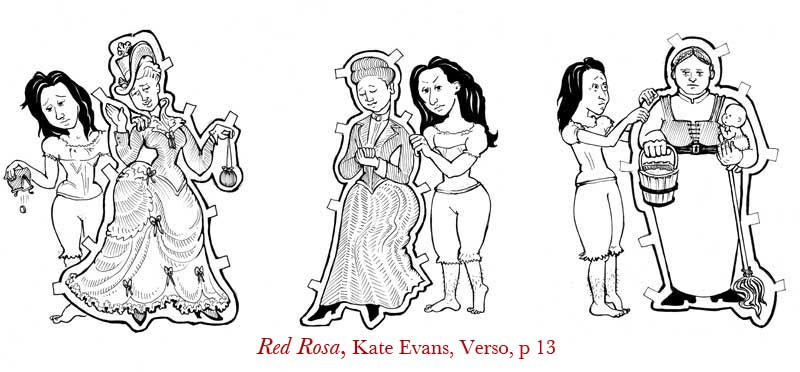

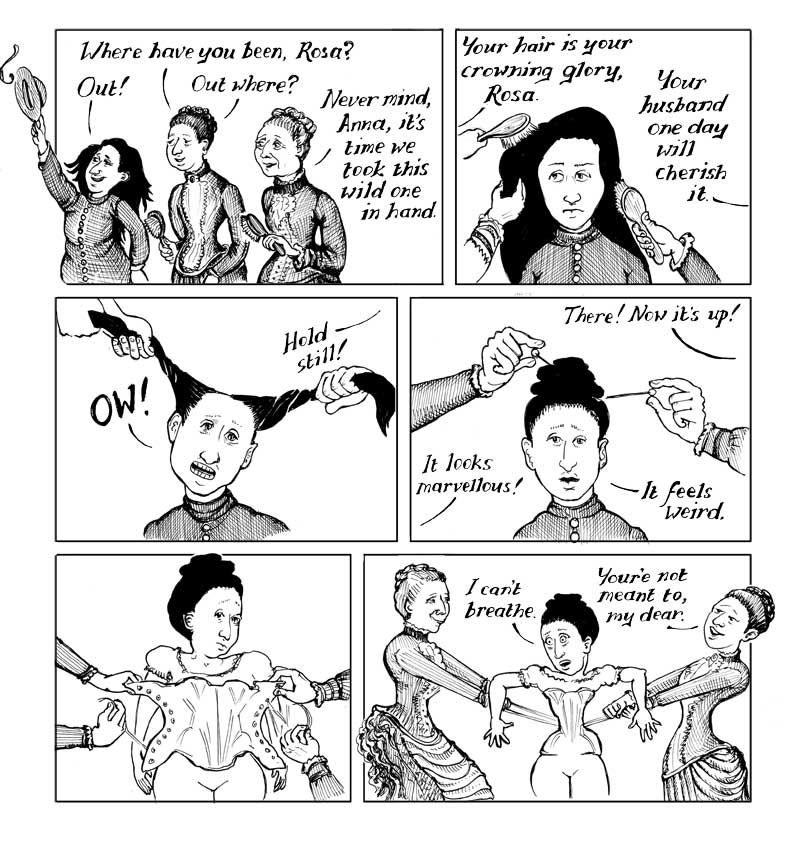

No biography of any 19th Century woman can effectively situate its subject for the reader without an explanation of the absolute primacy of patriarchy and the full extent of women’s subjugation. I set this out early on in the narrative.

As a woman [Luxemburg] is the legal property firstly of her father, and then of her husband. Women are commodities, and to trade well on the marriage market Rosa must have a fine dowry. Or failing that, graceful deportment, feminine charm, submissiveness and eagerness to please. Or as a last resort, strength, stamina for menial labour, and good childbearing hips.

A prodigious intellect, Rosa’s main asset, doesn’t enter into the balance sheet when calculating female worth. [Red Rosa p 13]

The ‘paper doll’ imagery shows how restrictive and limited are the acceptable avenues of female identity. Presenting the three different options shows how economic and cultural class shapes societal expectations and norms. (Note that I include Luxemburg’s body hair both for historical accuracy and also to challenge 21st century conventions about acceptable female body image.)

This is an abstract moment of exposition, but I also entwine the restrictions on adolescent Rosa into the narrative. In this scene I show how women can actively perpetuate and enthusiastically police the most repressive aspects of sexism.

The job of the graphic biographer is to compress life events into the fewest manageable frames (it’s a labour-intensive medium) and to maximise the drama of the events presented, so long as the work remains consistent with the known facts. This is how one engages the reader in the story. This representation of Rosa in corsets is a ‘set up’, giving the reader the reader the a priori knowledge that will inform their appreciation of Rosa’s later actions.

When we consult the historical record we find this iconic photograph of Luxemburg at the age of twenty two:

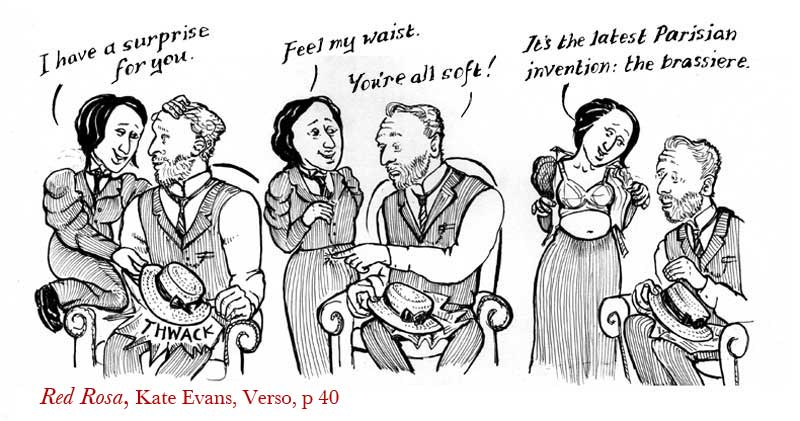

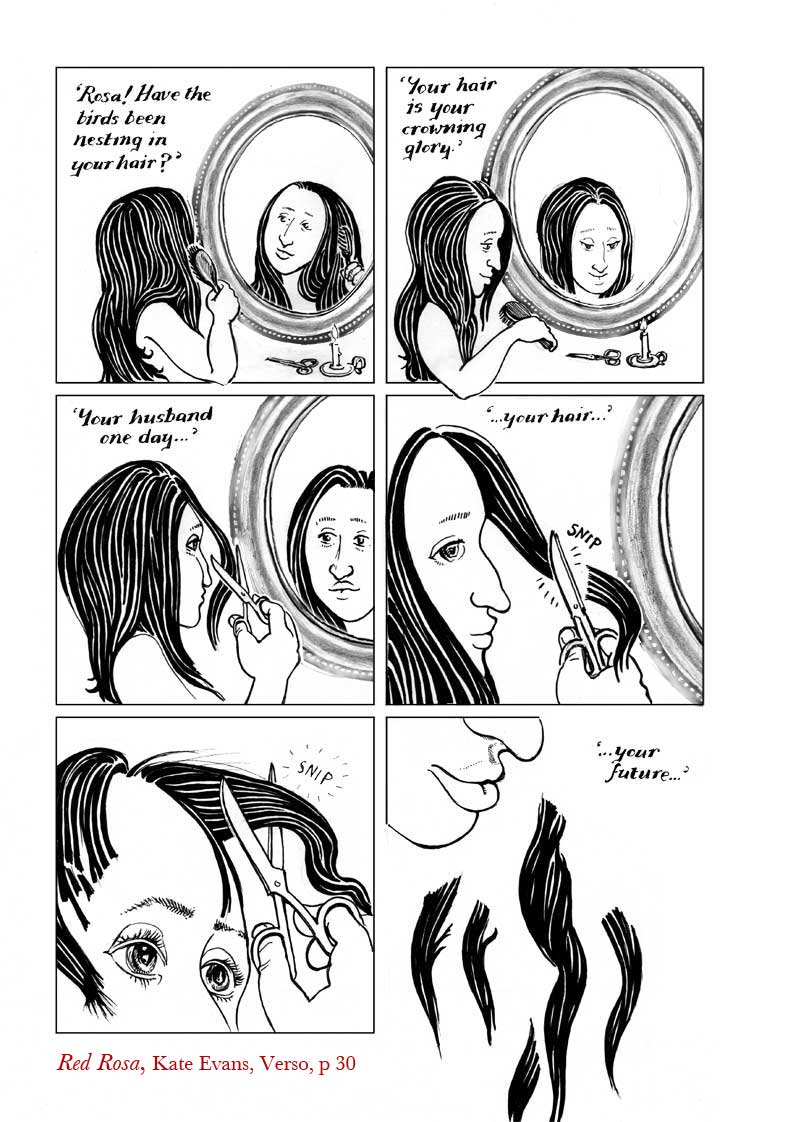

which, when combined with a telling reference in a personal letter: “I received the brassiere” [Letter to Leo Jogiches, March 29th 1894, p17, The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg, Verso 2011] reveals that the young adult Luxemburg rejected two of the ubiquitous signifiers of femininity, corsets and long hair.

Refusing to wear a corset in the late 19th Century was as radical as a 1960s feminist burning her bra.

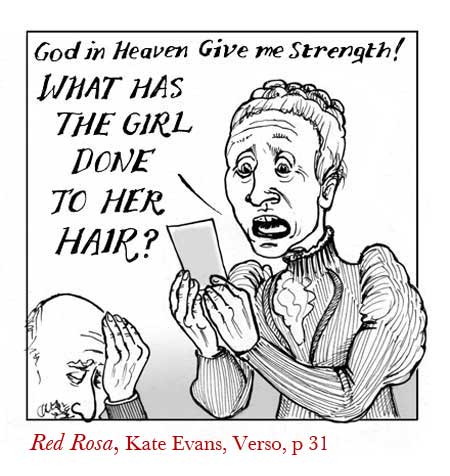

In the book cutting her hair becomes an explicit metaphor for Luxemburg’s rejection of society’s expectations of her as a woman: and in the interests of portraying the fullest representation of lived 19th Century womanhood, I also had to include her mother’s reaction to it.

and in the interests of portraying the fullest representation of lived 19th Century womanhood, I also had to include her mother’s reaction to it.

Plus, it’s funny. Comics are meant to be funny.

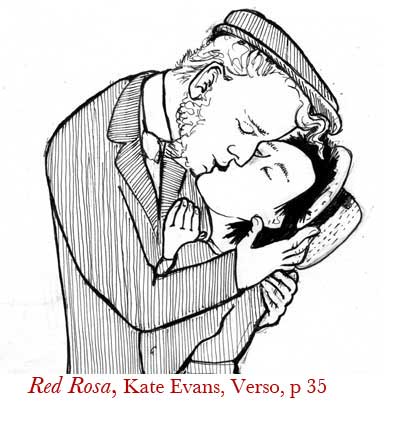

Despite having cut her hair Luxemburg is then shown embarking upon a romance, meeting ‘the man of her dreams’ Leo Jogiches. The presentation fits that familiar, conventional ‘boy meets girl’ trope and uses clichéd images of romance in so doing.

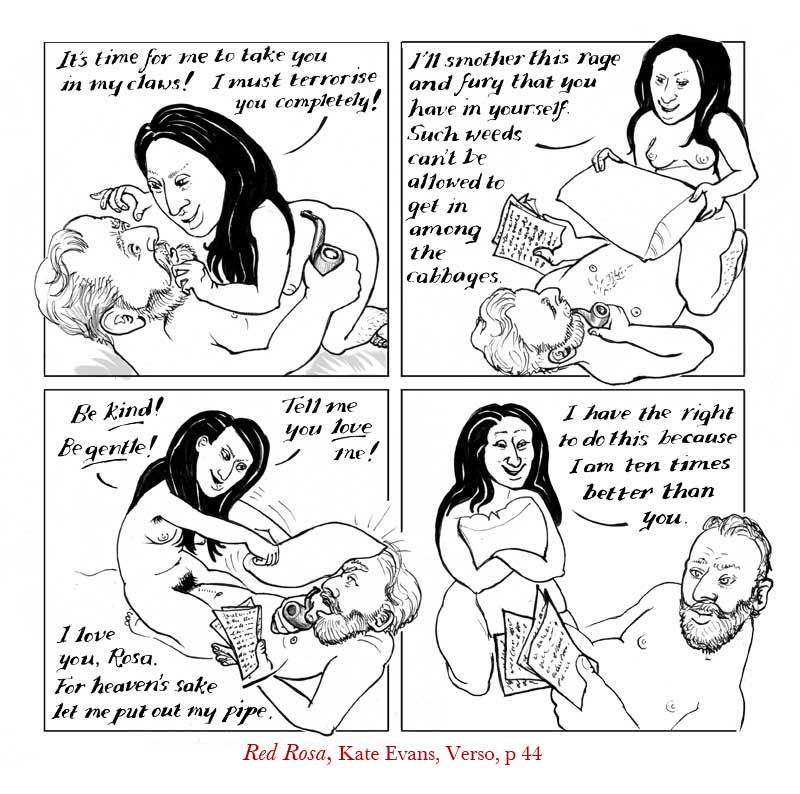

I particularly enjoyed crafting the romantic narrative in Red Rosa because Rosa and Leo do not live ‘happily ever after’. Luxemburg becomes increasingly frustrated with Jogiches’s emotional unavailability. The following excerpt uses Luxemburg’s actual words, which well deserve to be immortalised:

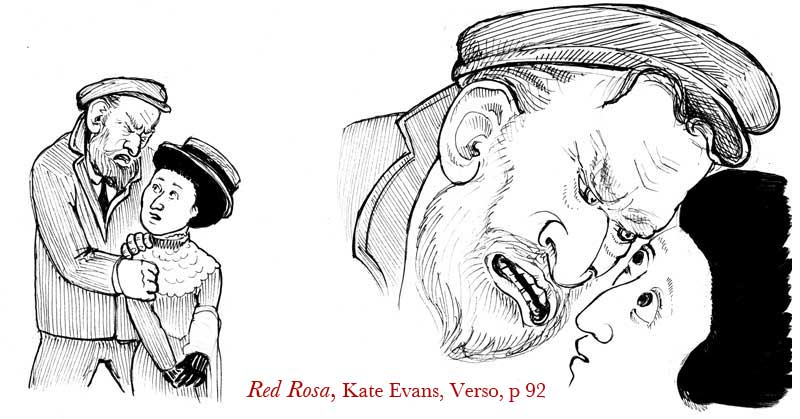

Their relationship degenerates and after their split, Jogiches subjects Luxemburg to sustained domestic abuse. The words in this sequence Leo Jogiches, while the images are informed by my personal experience of intimate partner violence:

“You’ll be staying here in London, even if in a hospital. You’re not going back to him. I would sooner strike you dead!” [Red Rosa p 92]

In my opinion, previous biographers of Luxemburg, Ettinger, Nettl and Frolich completely fail to address the seriousness of Luxemburg’s predicament at the point when Jogiches was stalking her. On the other hand feminist critiques which typify Jogiches as manipulative, controlling and classically abusive also misrepresent the unusual degree of equality that Luxemburg and Jogiches enjoyed. The famous feminist Clara Zetkin, Luxemburg’s close friend and contemporary, described Jogiches as being able to “tolerate a great female personality in loyal and happy comradeship, without feeling her growth and development to be fetters on his own ego”. [p 14, Rosa Luxemburg Paul Frolich, Haymarket Books 2010] That is not a description of a controlling, abusive relationship, regardless of how dysfunctional Jogiches’ reaction was to Luxemburg ending their affair. An understanding of the typical dynamics of domestic abuse within a patriarchal society is crucial for providing an accurate picture of the Luxemburg/Jogiches relationship, both to illustrate the ways in which their relationship was not abusive, as well as to accurately portray the point when it was.

Luxemburg goes on to have multiple lovers, some simultaneously. I particularly appreciated the opportunity to represent a historical female figure enjoying an active sex life. I speculate upon her use of contraception, provide inferred textual support for the depiction of her enjoying orgasm, and represent clitoral stimulation and positions other than the missionary position. There are even some penises. (The relative infrequency of representations of the male sexual organ in popular discourse is in itself sexist.) It is important for female artists to take full advantage of any opportunity to represent female sexual pleasure.

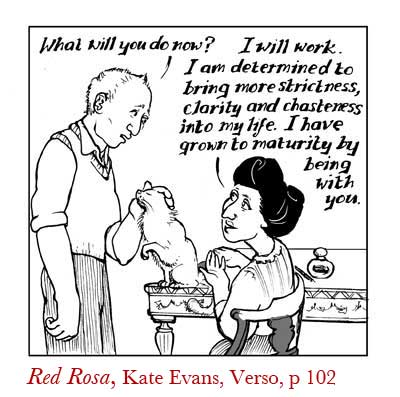

But it’s also important that we don’t prioritise the sexual and the relational when making representations of female agency. The following excerpt documents Luxemburg ending her relationship with lover, Kostya Zetkin (her friend Clara’s son): We don’t need to take Rosa’s declaration of chastity too seriously; Kostya is not her last lover. But, to pay her due credit as a woman grown to maturity, we could cease constructing her identity solely through the tired old trope of romance. There are bigger things in her life. [Red Rosa pp 102-3]

We don’t need to take Rosa’s declaration of chastity too seriously; Kostya is not her last lover. But, to pay her due credit as a woman grown to maturity, we could cease constructing her identity solely through the tired old trope of romance. There are bigger things in her life. [Red Rosa pp 102-3]

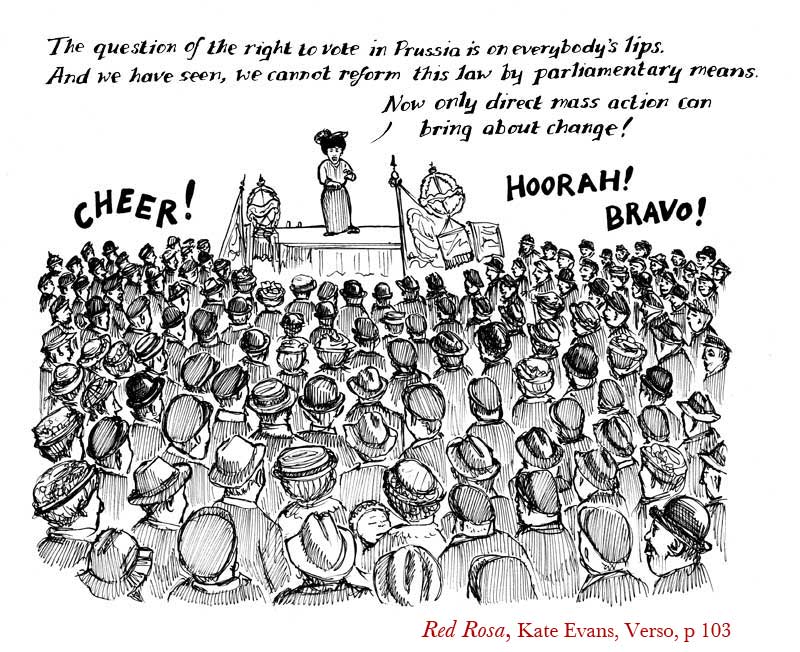

The real focus of the book is Rosa Luxemburg’s political activism, journalism, editorial work, academic successes, and her startlingly original and prescient theories of globalisation, the military-industrial complex, the causes of economic crises and theory of revolutionary spontaneity. I attempt to illustrate these as fully and as engagingly as the limited space permits. I use Luxemburg’s story to explore the economic realities of capitalism and to popularise Marxist critiques of it. So the book exhorts us to put our, quite natural, fascination with Luxemburg’s sex life aside and to concentrate on her ideas.

In and of itself, achieving forging a career as an academic and a revolutionary socialist in late 19thcentury/early 20th century Europe is an inspiring feminist achievement. There are aspects however, of Luxemburg’s identity as an academic and socialist theorist which intersect with her gender, and I tease these out too.

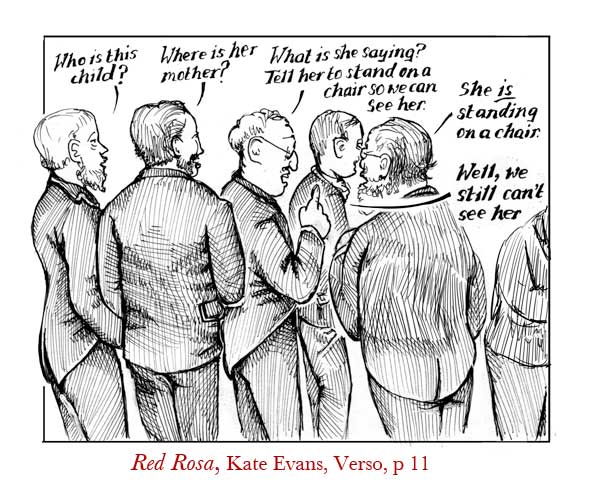

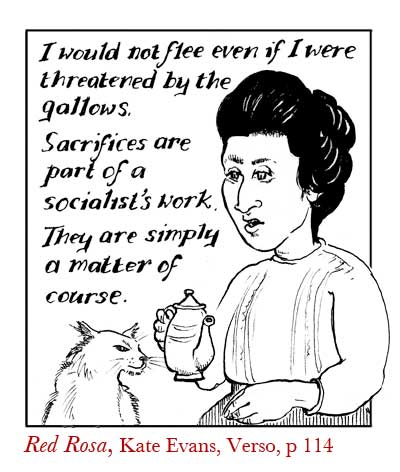

Luxemburg was extraordinarily young when she first became involved with socialism, possibly even still a schoolgirl. She was legally a child, and a girl child at that. Her sheer bravado in joining an overwhelmingly male political organisation at such a young age should be commemorated: She was a Polish Jew, Poland was part of Tsarist Russia, and the previous Tsar had been assassinated by Socialists. Political repression was severe, and Luxemburg carried with her throughout her life an expectation that she could be imprisoned or killed for her political beliefs.

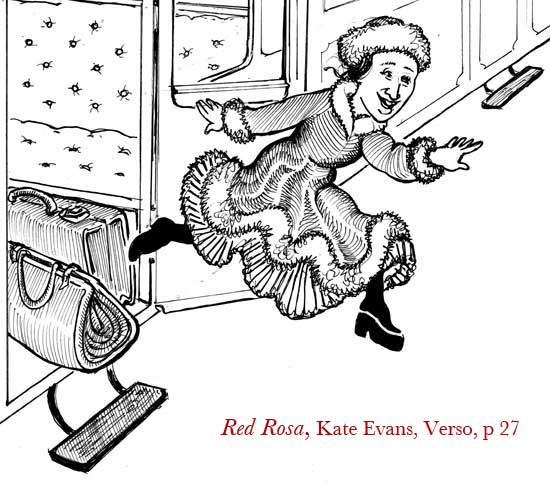

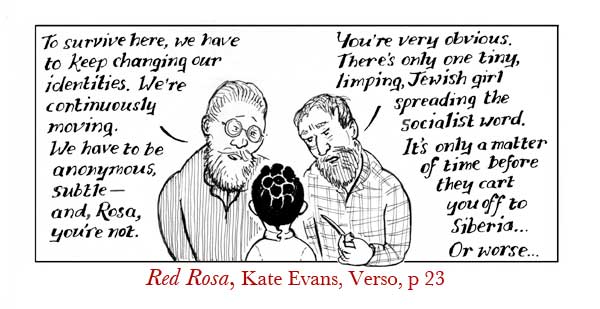

She was a Polish Jew, Poland was part of Tsarist Russia, and the previous Tsar had been assassinated by Socialists. Political repression was severe, and Luxemburg carried with her throughout her life an expectation that she could be imprisoned or killed for her political beliefs. Luxemburg was then forced into exile, still as a teenager, and I deduce that this was as a result of her gender, her disability, and her ethnicity, which made her visible to the secret police.

Luxemburg was then forced into exile, still as a teenager, and I deduce that this was as a result of her gender, her disability, and her ethnicity, which made her visible to the secret police. If on the one hand, her gender forces her into exile, it also provides a mechanism for her to immigrate into Germany. Luxemburg enters into a marriage of convenience with Gustav Lübeck in order to obtain German citizenship. It is questionable whether this option would have been available to a man. ‘Frau Gustav Lübeck’ becomes a second identity that Luxemburg assumes at times for convenience, just as she also confuses the authorities by juggling multiple dates of birth.

If on the one hand, her gender forces her into exile, it also provides a mechanism for her to immigrate into Germany. Luxemburg enters into a marriage of convenience with Gustav Lübeck in order to obtain German citizenship. It is questionable whether this option would have been available to a man. ‘Frau Gustav Lübeck’ becomes a second identity that Luxemburg assumes at times for convenience, just as she also confuses the authorities by juggling multiple dates of birth.

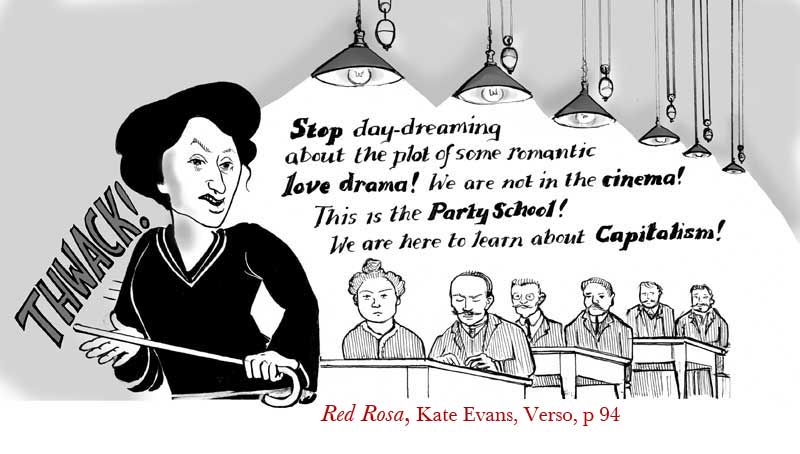

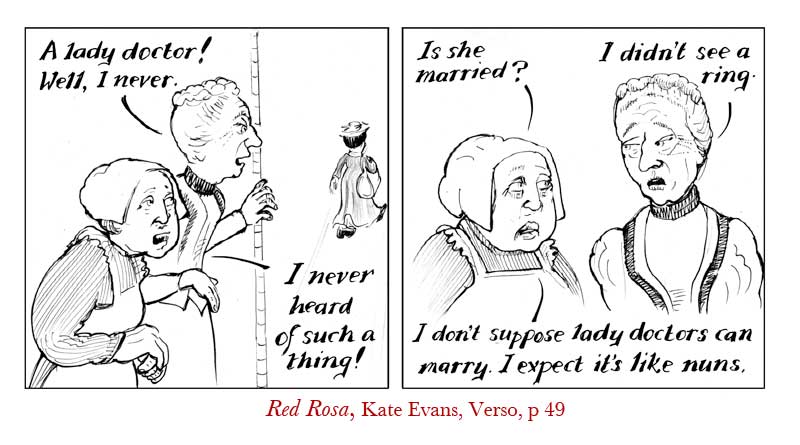

The most important identity that Luxemburg acquires, however, is the title of Dr. Her academic title enables her to be taken seriously in political sphere, and the androgynous gender identity it confers is played upon in the book. The following scene is inspired by a letter Luxemburg writes where she makes reference to a landlady who has “never seen a ‘Frau Doktor’ before” [Letters, ibid. p47]: In a sense, Luxemburg’s academic ambitions limit her willingness to engage with contemporary feminist debate. In order to be ‘allowed’ to engage in theoretical Marxist economics she must resist attempts from her peers to sideline her into ‘women’s issues’. And the women’s suffrage movement could also be guilty of prioritising the voices and the wishes of the privileged classes, which was anathema to Luxemburg with her keenly developed sense of class struggle.

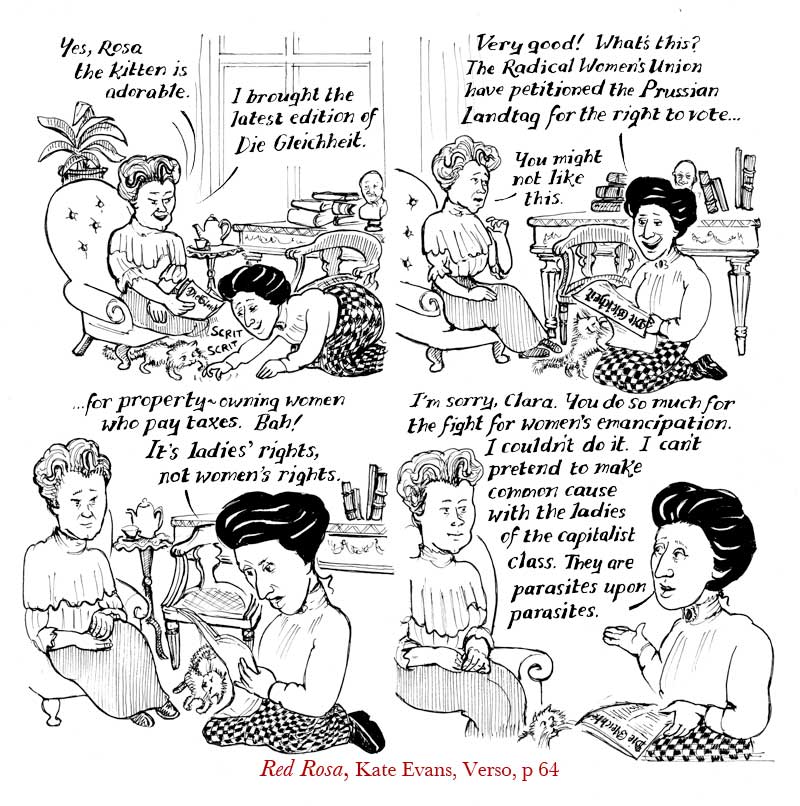

In a sense, Luxemburg’s academic ambitions limit her willingness to engage with contemporary feminist debate. In order to be ‘allowed’ to engage in theoretical Marxist economics she must resist attempts from her peers to sideline her into ‘women’s issues’. And the women’s suffrage movement could also be guilty of prioritising the voices and the wishes of the privileged classes, which was anathema to Luxemburg with her keenly developed sense of class struggle. Ultimately, sexism has seriously affected appreciation of Luxemburg’s economic genius. Her Collected Works are only now being collated by Verso, translated into English and published in full. And reading Luxemburg’s Anti-Critique, in which she discusses the hostile reception that her epic work The Accumulation of Capital received in the contemporary socialist press, it becomes clear that she provoked enmity from her male peers, partly based on her ethnicity and her gender.

Ultimately, sexism has seriously affected appreciation of Luxemburg’s economic genius. Her Collected Works are only now being collated by Verso, translated into English and published in full. And reading Luxemburg’s Anti-Critique, in which she discusses the hostile reception that her epic work The Accumulation of Capital received in the contemporary socialist press, it becomes clear that she provoked enmity from her male peers, partly based on her ethnicity and her gender.

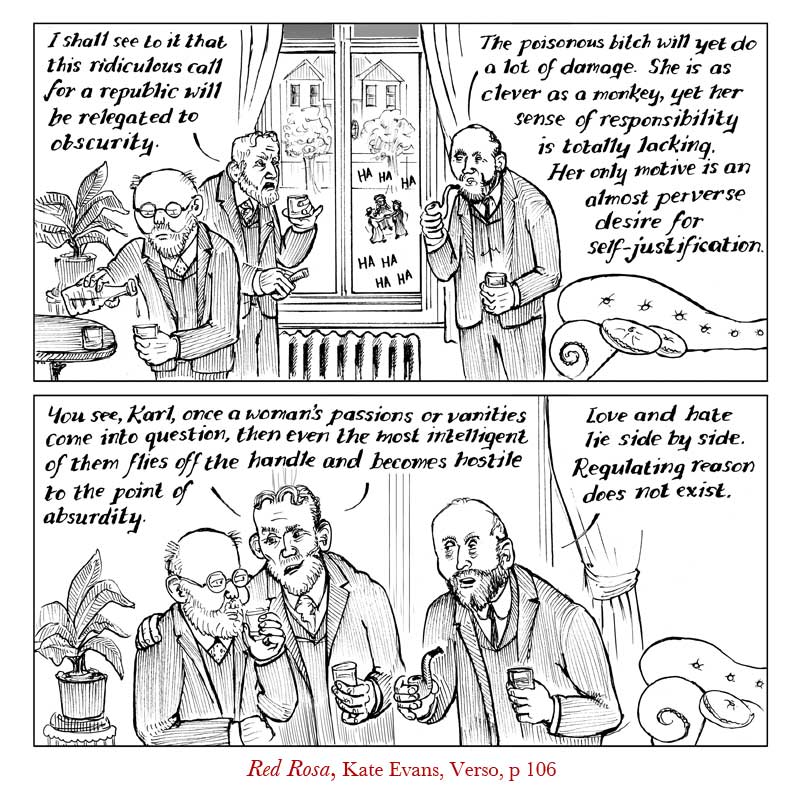

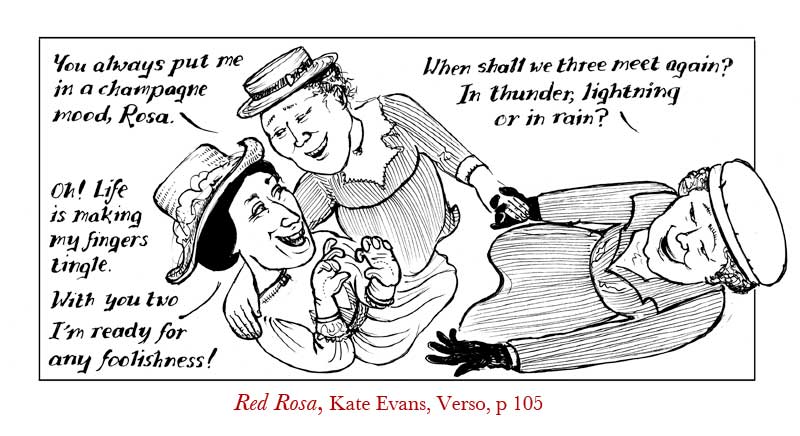

The following is based on a verbatim conversation between August Bebel, author of the feminist workWomen Under Socialism, and another prominent socialist Victor Adler: In the background in the first frame we can glimpse Rosa with her good friends Luise Kautsky and Clara Zetkin. The vitriol of the men in this sequence stands in stark contrast with the laughter and love between the women outside the window.

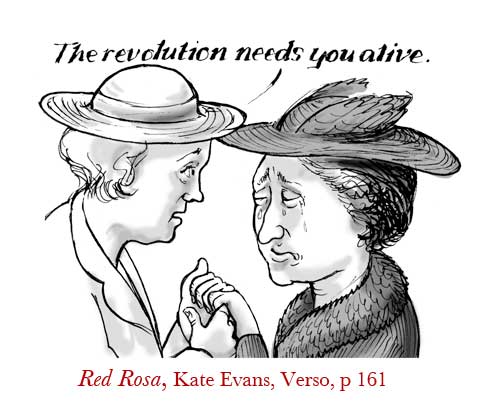

In the background in the first frame we can glimpse Rosa with her good friends Luise Kautsky and Clara Zetkin. The vitriol of the men in this sequence stands in stark contrast with the laughter and love between the women outside the window. Rosa Luxemburg was a theorist of revolutions because she actively participated in them. She analysed the 1905 Russian revolution from the streets of Warsaw under martial law. She was instrumental in building the movement that led to the German revolution and the Spartakist uprising. The representations of the German revolution that form the climax of the book are largely based upon documentary photos of historical figures and scenes, but they are knitted together with a recurring image of Rosa Luxemburg and Mathilde Jacob that gives me a particular sense of pride.

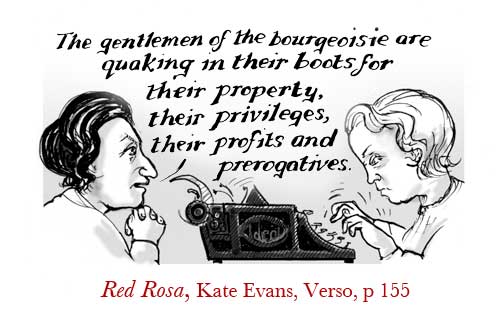

Rosa Luxemburg was a theorist of revolutions because she actively participated in them. She analysed the 1905 Russian revolution from the streets of Warsaw under martial law. She was instrumental in building the movement that led to the German revolution and the Spartakist uprising. The representations of the German revolution that form the climax of the book are largely based upon documentary photos of historical figures and scenes, but they are knitted together with a recurring image of Rosa Luxemburg and Mathilde Jacob that gives me a particular sense of pride. Here are two middle-aged women making a revolution. Not on the barricades with guns but with words and typewriters. Rosa Luxemburg was as great as she was because she was part of a movement, and it’s a pleasure to be able to represent some of the other people who enabled her. People like Mathilde Jacob whose secretarial and organisational contribution to the Socialist cause has been consistently underestimated.

Here are two middle-aged women making a revolution. Not on the barricades with guns but with words and typewriters. Rosa Luxemburg was as great as she was because she was part of a movement, and it’s a pleasure to be able to represent some of the other people who enabled her. People like Mathilde Jacob whose secretarial and organisational contribution to the Socialist cause has been consistently underestimated. Rosa Luxemburg dies, of course.

Rosa Luxemburg dies, of course.

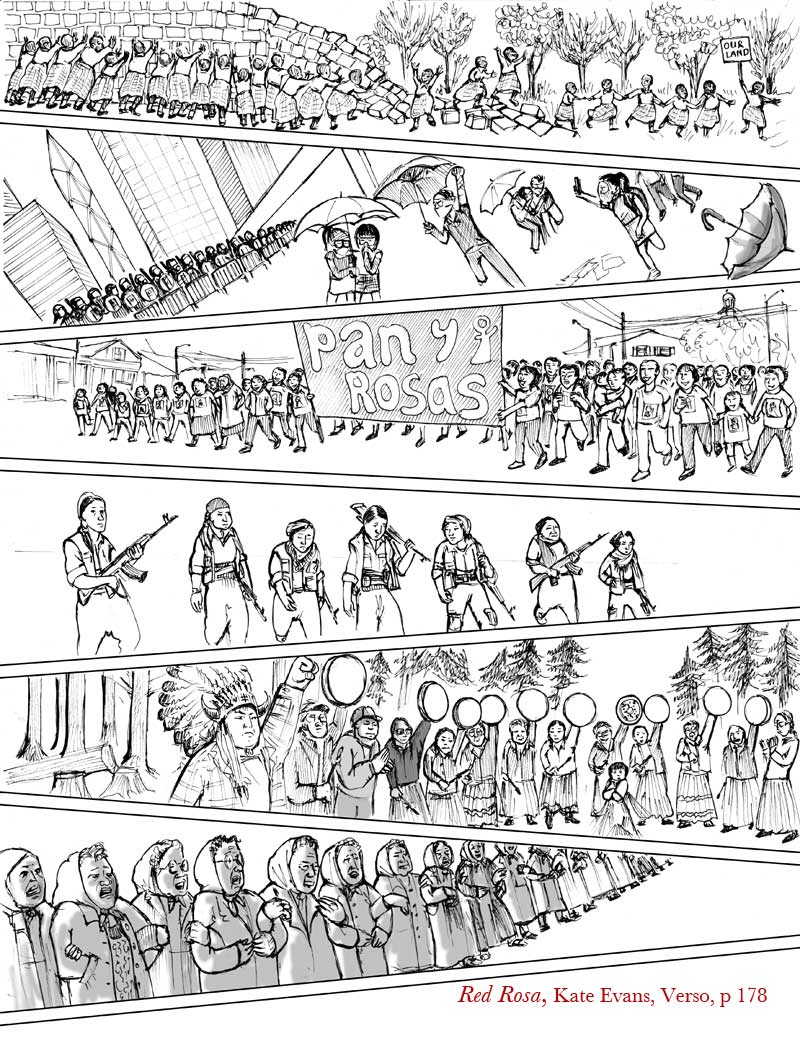

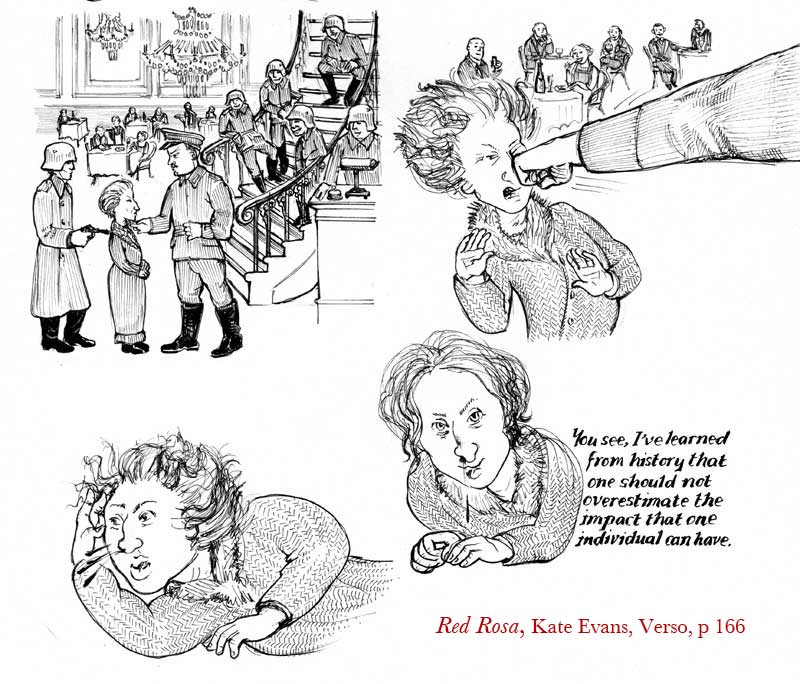

An exclusive focus on the individual could be seen as itself, capitalist and patriarchal. I hope that my book comes some way to promoting Rosa in relation to her ideas, to her comrades, to a community. Rosa breaks the fourth wall in the moments before the representation of her murder with a quote about the dangers of individualism:

And it’s in that spirit of popular mass uprising that I illustrate her legacy in the final pages with a sequence of pictures of predominately female activism from people of all ages around the globe. Luxemburg’s message only becomes more relevant as another inherent crisis of capitalism looms and the onward march of globalisation and militarism produces more victims, human and ecological. I hope my telling of her story inspires others to join the fight. The fight for bread, and for Rosas too.

And it’s in that spirit of popular mass uprising that I illustrate her legacy in the final pages with a sequence of pictures of predominately female activism from people of all ages around the globe. Luxemburg’s message only becomes more relevant as another inherent crisis of capitalism looms and the onward march of globalisation and militarism produces more victims, human and ecological. I hope my telling of her story inspires others to join the fight. The fight for bread, and for Rosas too.