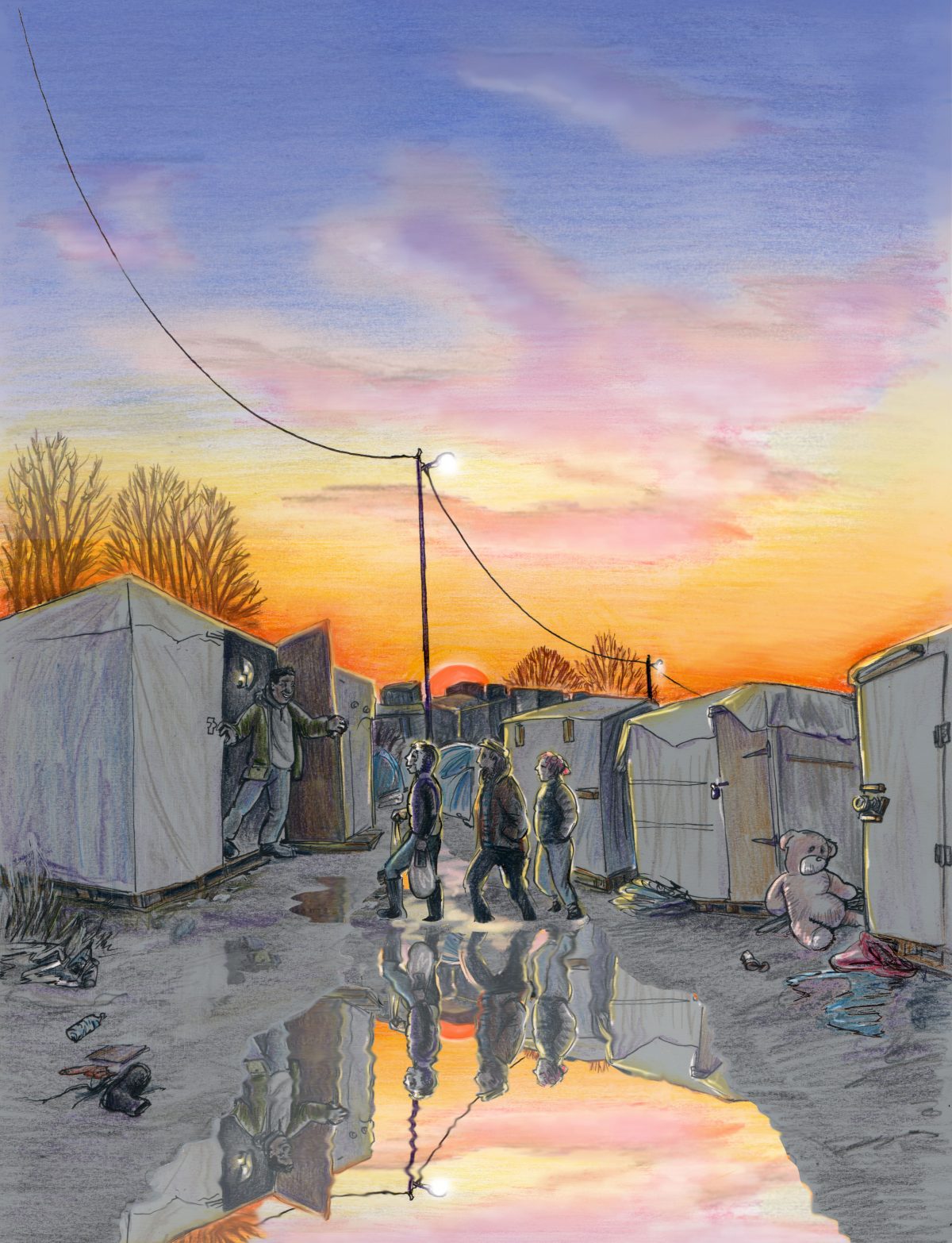

How does it feel to be a refugee in Calais? To be living in a tent in the shantytown known as the Jungle? Who are these people who have risked everything on the chance of a new life?

These are the questions cartoonist Kate Evans asks in her new book Threads. An example of graphic reportage, Evans went and worked in Calais, listened to the stories of the people who lived there, saw how they were treated by the police and politicians. Out of it has come a book that is sometimes angry, sometimes heart-breaking, but also nuanced and thoughtful.

Here, Kate Evans talks about her experiences in the Jungle and why cartoons are such a potent form for journalism.

What took you to Calais in the first place?

A friend was going, she booked a flat to stay in and offered me a space in her car. It was only a weekend trip. But of course I had to go back again after that.

What were your first impressions? How long did you stay? What did you do when you were there?

Well, it was pretty overwhelming. There were a lot of first impressions. Fortunately, as a graphic novelist, I have a detailed way in which to record them. That first three-day visit became a 16-page cartoon, first a blog post, then a printed comic, and then finally it formed the first chapter of Threads.

We wanted to be helpful in every way we could; we helped with building shelters, picked up rubbish and helped with the sorting and distribution of aid. And I drew some portraits for people. I figured it would be nice to give someone a hand drawn picture – it’s a way of recognising someone’s humanity.

The book manages to convey the everyday normality of the place and its ongoing terrors at the same time. Is that how you see it?

I always look for the personal stories in political events – it’s my take on the feminist slogan “the personal is political”. And there is always something funny, or wry, or silly as well as something serious going on wherever you go. I think it’s important to retain the humour as much as possible. I structure my work carefully so that the narrative takes the reader up as well as down.

Of all the people you met during your time there who has stayed with you most?

The book contains the personal stories of some of the refugees that I met there, and I do get asked “what happened to them?” I think it’s quite important to respect the fact that these are representations of a real people, who are very vulnerable. I never answer when someone asks what happened to them. I think it’s better to leave the story open-ended, because any number of outcomes could have happened to any of these people, good or bad.

However, I can namecheck one guy I originally met at the camp, the artist Majid Ad. He has successfully claimed asylum here in the UK and has won an international animation competition to create the official video for Elton John for the song Rocket Man. It has had seven million views in a month. His work is astonishingly good.

I’ve carried on working with Bristol Refugee Rights here in the UK since the book was published. I’ve been researching the impact of the new Immigration Act which is designed to make refugees homeless and destitute, and increase discrimination against asylum seekers and immigrants of all kinds. The most important stories about refugees in the UK may be the ones that haven’t yet been told.

The politics that swirl around the place is unrelenting. Is Threads an attempt to “rehumanise” the numbers and controversy?

Of course it is. Because it isn’t about numbers, it’s about people, and when we lose sight of basic humanitarian principles of freedom of movement and giving refuge to those who require it, we all suffer.

What do you think approaching this story in graphic form allows you to do that other forms might not?

Graphic reportage is a wonderfully flexible medium for telling a story from a crisis situation. It enables me to create a narrative about real people and real events, but to disguise the details of the people involved, completely seamlessly, in order to protect their identities. You couldn’t film a story of life in the Calais Jungle – carrying a film camera into someone’s home there would be too intrusive.

Also, since the Dublin regulations require people to claim asylum in the first European country they enter, this means that people have to hide their identities, stay off the radar, until they reach their destination. So taking photos or filming someone’s face in Calais is usually inappropriate.

But it’s not just about the minutiae of people’s stories. I can weave multiple narratives together, tell stories from different angles, and juxtapose the real stories of real people with hostile political opinions, giving the lie to the snap assumptions that racists make about the migrants seeking to ‘invade’ our shores. I love drawing graphic novels. Which is a good thing, really, because it’s insanely labour-intensive, and doesn’t leave me much of a social life.

Has the experience changed you, do you think?

Yes, it has. It has made me so much more grateful.

Before I went and spent time at the Calais Jungle, I used to look at my children lying safe in their beds, and think of the kids out in Calais, and Paris, and Serbia, and Greece, and I would feel so guilty, so sad, that my children were warm while others were freezing. I don’t feel that now. I feel lucky. I realise how precious it is to have a safe, stable, loving place to raise my family. I don’t take it for granted.

This interview first appeared in the Sunday Herald, June 19th 2017.